I decided at the beginning of 2006 to try to keep up with the books I read during the year. Below is a list that I think must be incomplete, since I don’t believe I wrote everything down. First are the books that I read completely, followed by a second list of books that I read only in part, which could mean anything from a few paragraphs to a couple hundred pages. The fact that I only read part of a book does not imply that it was a bad book or couldn’t keep my attention (though in some cases that is true); rather, it means that, for one reason or another, I wasn’t able to complete it at the time. Sometimes I have to stop what I’m doing and read something related to a writing project I'm engaged in. Sometimes a discussion with a friend or family member prompts me to read something to be better informed on the subject. Sometimes I just pick up an old favourite and just jump into it for a random chapter or two. At times I just don’t get back to the previous book, or at least for a while.

I decided at the beginning of 2006 to try to keep up with the books I read during the year. Below is a list that I think must be incomplete, since I don’t believe I wrote everything down. First are the books that I read completely, followed by a second list of books that I read only in part, which could mean anything from a few paragraphs to a couple hundred pages. The fact that I only read part of a book does not imply that it was a bad book or couldn’t keep my attention (though in some cases that is true); rather, it means that, for one reason or another, I wasn’t able to complete it at the time. Sometimes I have to stop what I’m doing and read something related to a writing project I'm engaged in. Sometimes a discussion with a friend or family member prompts me to read something to be better informed on the subject. Sometimes I just pick up an old favourite and just jump into it for a random chapter or two. At times I just don’t get back to the previous book, or at least for a while.Apart from grouping an author’s books together, these are in no particular order. Short stories are included in the second list, as they don't represent an entire book read.

What were your favourite books during the year?

Here are the books read entirely:

1. The Everlasting Man (G.K. Chesterton)

2. The Flying Inn (G.K. Chesterton)

3. Four Faultless Felons (G.K. Chesterton)

4. The Man Who Was Thursday (G.K. Chesterton) (3rd time)

5. The Club of Queer Trades (G.K. Chesterton)

6. The Man Who Knew Too Much (G.K. Chesterton)

7. Lepanto (G.K. Chesterton)

8. Wise Blood (Flannery O’Connor)

9. The Da Vinci Code (Dan Brown)

10. Wise Words: Family Stories That Bring the Proverbs to Life (Peter Leithart)

11. Against Christianity (Peter Leithart)

12. Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone (J.K. Rowling) (2nd time)

13. Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets (J.K. Rowling) (2nd time)

14. Carry On, Jeeves (P.G. Wodehouse) (2nd time)

15. Very Good, Jeeves (P.G. Wodehouse) (2nd time)

16. Jeeves in the Morning (P.G. Wodehouse)

17. The Magician’s Nephew (C. S. Lewis) (Can't remember how many times)

18. The Silver Chair (C.S. Lewis) (Can't remember how many times)

19. Taliessin Through Logres/The Region of the Summer Stars/Arthurian Torso (Charles Williams/C.S. Lewis)

20. War in Heaven (Charles Williams)

21. The Last Disciple (Hank Haanegraaff and Sigmund Brouwer)

22. The Essential Calvin and Hobbes (Bill Watterson)

23. Yukon Ho (Bill Watterson)

24. The Leper of St Giles (Ellis Peters)

25. Godless: The Church of Liberalism (Ann Coulter)

26. For All the Saints? Remembering the Christian Departed (N.T. Wright)

27. More Than a Skeleton (Paul Maier)

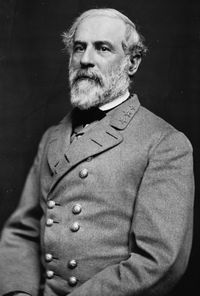

28. Never Call Retreat: Lee and Grant: The Final Victory (Newt Gingrich/William R. Fortschen)

29. Cricket on the Hearth (Charles Dickens)

30. America Alone: The End of the World As We Know It (Mark Steyn)

31. Zeal of Thy House (Dorothy L. Sayers) (4th time)

Here are the books that were regrettably (in most cases) unfinished:

1. The Foresters: Robin and Marian (Alfred Lord Tennyson)

2. The Challenge of Jesus: Rediscovering Who Jesus Was and Is (N.T. Wright)

3. The Crown and the Fire: Meditations on the Cross and the Life of the Spirit (N.T. Wright)

4. The Case for Covenant Communion (Greg Strawbridge)

5. The Case for Covenantal Infant Baptism (Greg Strawbridge)

6. Paedofaith: A Primer on the Mystery of Infant Salvation and a Handbook for Covenant Parents (Rich Lusk)

7. The Federal Vision (Steve Wilkins/Garner)

8. The River/Good Country People/The Displaced Person/Wildcat/A Good Man is Hard to Find/A Temple of the Holy Ghost (from O’Connor: Collected Works, Flannery O’Connor)

9. Trinity and Reality: An Introduction to the Christian Faith (Ralph Smith)

1o. A Generous Orthodoxy: Why I am a Confused, etc, Christian (Brian McLaren)

11. Lee and Jackson: Confederate Chieftains (Paul D. Casdorph)

12. How the Irish Saved Civilization: The Untold Story of Ireland’s Heroic Role from the Fall of Rome to the Rise of Medieval Europe (Thomas Cahill)

13. Lillith (George MacDonald)

14. The Wise Woman (George MacDonald)

15. The Valley of Fear (Sir Arthur Conan Doyle)

16. The Abominable History of the Man with Copper Fingers (from Lord Peter: The Complete Lord Peter Wimsey Stories, Dorothy L. Sayers) (2nd time)

17. Creed or Chaos (Dorothy L. Sayers)

18. Henry V (William Shakespeare)

19. The Return of the King (J.R.R. Tolkien)

20. Descent Into Hell (Charles Williams)

21. How Right You Are Jeeves (P.G. Wodehouse)

22. The Most of P.G. Wodehouse (P.G. Wodehouse)

23. City of God (Augustine)

24. A Reformation Debate (John Calvin, Jacopo Sadoleto)

25. The Origin of Species By Means of Natural Selection or The Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life (Charles Darwin)

26. How Should We Then Live: The Rise and Decline of Western Thought and Culture (Francis Schaeffer)

27. Knowing God (J.I. Packer)

28. Demon Possession (ed, John Warwick Montgomery)

29. More Liberty Means Less Government: Our Founders Knew This Well (Walter Williams)

30. Omnibus III: Reformation to the Present (ed, Douglas Wilson and Ty Fischer, with a contribution by Yours Truly)

31. Mother Kirk: Essays and Forays in Practical Ecclesiology (Douglas Wilson)

32. Federal Husband (Douglas Wilson)

33. My Life For Yours: A Walk Through the Christian Home (Douglas Wilson)

34. The Oxford History of Christian Worship (ed, Geoffrey Wainwright and Karen B. Westerfield Tucker)

35. From Cottage to Workstation: The Family’s Search for Social Harmony in the Industrial Age (Allan C. Carlson)

36. Letters to Malcolm: Chiefly on Prayer (C.S. Lewis)

37. God in the Dock: Essays on Theology and Ethics (C.S. Lewis)

38. The Pilgrim’s Regress: An Allegorical Apology for Christianity Reason and Romanticism (C.S. Lewis)

39. The Gospel According to Tolkien: Visions of the Kingdom in Middle-earth (Ralph Wood)

40. The Encyclopaedia of the Middle Ages (Norman Cantor)

41. Bullfinch’s Mythology: The Age of Chivalry (Thomas Bullfinch)

42. Piers Plowman (William Langland)

43. The Writer’s Digest Handbook of Novel Writing

44. General Washington’s Christmas Farewell: A Mount Vernon Homecoming 1783 (Stanley Weintraub)

45. Our Nation’s Archive: The History of the United States in Documents (ed, Erik Bruun and Jay Crosby)

46. The Journals of Lewis and Clark (Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, ed, Anthony Brandt)

47. The Real Lincoln: A New Look at Abraham Lincoln, His Agenda, and an Unnecessary War (Thomas J. DiLorenzo)

48. Lincoln Unmasked: What You’re Not Supposed to Know About Dishonest Abe (Thomas J. DiLorenzo)

49. An Honourable Defeat: The Last Days of the Confederate Government (William C . Davis)

Theodore Roosevelt (Louis Auchincloss)

50. Southern Tales (Webb Garrison)

51. Scotland: The Story of a Nation (Magnus Magnusson)

52. Scotland: A Short History (Christopher Harvie)

53. 1314: Bannockburn (Aryeh Nusbacher)

54. Troubadour for the Lord: The Story of John Michael Talbot (Dan O’Neill)

55. In the Arena: An Autobiography (Charlton Heston)

56. The Size of Chesterton’s Catholicism (David W. Fagerberg)

57. Crossing the Threshold of Hope (John Paul II)

58. Triumph: The Power and the Glory of the Catholic Church (H.W. Crocker III)

59. The Blood of the Moon: The Roots of the Middle East Crisis (George Grant)

60. The Autobiography of G.K. Chesterton (G.K. Chesterton)

61. Glory and Honor: The Musical and Artistic Legacy of Johann Sebastian Bach (Gregory Wilbur)

62. Michelangelo and the Pope’s Ceiling (Ross King)

63. Stonewall Jackson: The Black Man’s Friend (Richard G. Williams, Jr)

64. Roosevelt: Letters and Speeches (Theodore Roosevelt)

65. America: The Last Best Hope, Vol I: From the Age of Discovery to a World at War (William J. Bennett)

66. American Courage: Remarkable True Stories Exhibiting the Bravery That Has Made Our Country Great (ed, Herbert W. Warden III)

67. Confederate Emancipation: Southern Plans to Free and Arm Slaves During the Civil War (Bruce Levine)

68. Encyclopedia Brown and the Case of the Secret Pitch (Donald J. Sobol)