Saturday, December 10, 2005

Days of Old Long Ago

On the vigil, we sing 'Should auld acquaintance be forgot, and days of auld lang syne'. Few, perhaps, know this Scots phrase, meaning, ‘old long ago.’ We remember, we sigh for the good old days, even while resolving to live better in days to come. We laugh, and kiss, and party, celebrating Time’s changing of the guard. We drink a cup o' kindness, for days of old long ago.

But while Dick Clark and ABC are still in the planning stages for the next Rockin’ New Year’s Eve, another New Year’s Day recently slipped quietly by, as it does each year, largely unnoticed by the revelers, waiting in the wings. Near the beginning of December, the Church Year began again, with the dawning of the Advent Season. The Christian Church marks the passing of time by remembering the Days of Redemptive History: the life of Christ. Advent, Christmas, Epiphany, Palm Sunday, Easter, Pentecost, the Ascension—we pass from waiting to fulfillment, from sorrow to sorrow and joy to joy. The mourning of Tenebrae on Good Friday is shattered by the trumpet blasts of triumphant rejoicing on Resurrection Sunday. We remember the Trinity, Christ the King, the Holy Innocents. We repent during the Lenten Season and feast during the Christmas season.

A friend of mine says the Church Calendar should always be at war with that of the unbelieving world, at least until the former shapes the latter. In other words, the Church should always hold to its own days, while observing civic holidays only after consideration, and then, perhaps, not even on the same days: he even suggested that perhaps we should always observe alternate days—Thanksgiving on Friday, for instance—to make the point that the Church is not subject to the State in such matters. Others say that the Church Year is only tradition, and not required by Scripture. Though this is true, the example of a liturgical calendar can still be found in the pages of Holy Writ, while Jesus Himself attended religious festivals not required by the Law.

But wherever a church finds itself on this spectrum of opinion, it is certainly true that for Christians—wary of mere tradition, but never afraid of it—the more important New Year should be obvious, though I am not saying it is a sin to hang a January-December calendar on the wall (for the sake of convenience, if nothing else; we’re not yet to the point where you can call your doctor to see if he has anything open the second Tuesday after Trinity). Surely even those whose churches don’t observe the Church Calendar can see the contrast between the two ways of marking time: Sosigenes’ mathematical divisions of days—or the events of the life and work of Jesus. ‘Thirty days hath September,’ or the birth, life, miracles, death, resurrection, and ascension of the Messiah—great deeds in days of Auld Lang Syne.

Happy New Year.

Saturday, November 26, 2005

What's New

Stay tuned, for there is more to come.

Thursday, November 24, 2005

Talking of Dragons on Blog and Mablog

Doug Wilson was kind enough to write a blurb for my forthcoming book, Talking of Dragons (for which, see here). He keeps a Book Log on his website, on which he lists books he has read, along with the author's name, and his one or two word label for it: 'Excellent'; 'Really Good'; 'Whattabook'; 'Atrocious'; 'Appalling'; 'Bleh'; and so on. He listed Talking of Dragons in September's Book Log, with the epithet, 'Really Good', which was very gratifying, of course. I highly recommend his blog (wonderfully titled 'Blog and Mablog'). It will make you think, laugh, and, quite possibly, howl with rage. Check it out here.

Friday, October 28, 2005

Start at the Beginning

Seeing Christ in all of Scripture

Many thanks to Kerry Lewis for helpful suggestions that greatly improved this article.

OK, so this guy walks into a bookstore (stop me if you’ve heard this one) and after absolutely no searching at all, finds a huge display with about four thousand copies of the Harry Potter books. He’s hasn’t read any of the six titles released so far, but has finally succumbed to cultural peer-pressure and decided to see what all the fuss is about. He buys one of each and heads for home.

Back at the house, he has all six books spread out on his coffee table. They all have interesting covers and he ponders where to begin. Finally, he notices that each of them seems to have some sort of chronological designation: year one, year two, and so on. But he likes the cover of book 4 better than book 1, so he decides to begin there. Puzzled by the end, he then skips to the newest entry, book 6, and reads that one. Even more confused, he next reads book 5, but there is obviously a back-story he is missing, so he goes back to book 2, then, 3, and finally, book 1. At last, he chunks them all in the trash, deciding that if the author can’t make herself clearer than that, she should find another job.

Ridiculous, you say? Unreasonable? I agree, but why? Obviously, because, though there are many books in the Harry Potter series, there is only one story. Those who start in the middle are bound to be confused. Not only will they misunderstand what’s going on, they will actually miss a lot of it. No one would recommend that a new reader start in the middle of a story.

No one, that is, except Christians. What’s the first thing we do with a new believer? Why, send them to the Gospel of John, of course, which, in some ways, is just like starting with book 4 of Harry Potter.

“But,” some will say, “that’s because we want new Christians to start with the story of Jesus, the most important part of the Bible, and not get confused with a lot of stuff that doesn’t have anything to do with Him!”

Now, it is perfectly true that we should start our Bible reading with the story of Jesus. The question is: where does this story begin? “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. He was in the beginning with God. All things were made through him, and without him was not any thing made that was made” (John 1:1-3). The Word, of course, is Jesus Christ. According to St John, He was “in the beginning” and indeed, the one through whom “all things were made.” The story of Christ, then, begins, not in first century Bethlehem, but before the world was made. Not in John 1, but in Genesis 1.

So, yes, by all means, let new readers begin their reading with the story of Jesus; but you must realize that this will include, not only the Gospels or Epistles, but the writings of the Old Testament as well. Put another way, there is only one story in the Bible, and it is all about Jesus Christ.

Surprised? Perhaps you have been taught, like many, that the Old Testament is a lot of confusing stuff that doesn’t relate to “New Testament” Christians. Before answering that objection, I should probably point out that I am not saying “don’t read the New Testament until you’ve read the Old.” For children, especially, a focus on the narratives of Christ’s Incarnation, the days when He walked the earth, is essential. Any good Bible teaching plan should do that. In addition, it would be beneficial to include appropriate passages from the letters of Paul, or John, or Peter (to help understand the significance of the story of Christ), and readings from the Old Testament, including a generous portion of the Psalms (to help understand the context of the story of Christ). Whatever you do, don’t just skip the Old Testament, or treat it as something completely alien to the New Testament accounts.

But again, what does the Old Testament have to do with the story of Jesus in the New Testament? Scripture itself teaches us the connection. After His resurrection, Jesus walked with two disciples on the road to Emmaus. Luke tells us that, “…beginning with Moses and all the Prophets, he interpreted to them in all the Scriptures the things concerning himself.” (Luke 24:27) Note carefully what is said here. Jesus goes through the Old Testament (“Moses and all the Prophets”) and shows them “the things concerning himself.”

On another occasion, the Jews asked Jesus (who had just informed them that “if anyone keeps my word, he will never taste death”), “Are you greater than our father Abraham, who died?” Jesus responded:

“Your father Abraham rejoiced that he would see my day. He saw it and was glad.” So the Jews said to him, “You are not yet fifty years old, and have you seen Abraham?” Jesus said to them, “Truly, truly, I say to you, before Abraham was, I am.” (John 8:53, 56-58)

Here we see Christ’s claim to be the eternal God, “I Am,” who revealed His name to Moses and said he was the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob (Exodus 3:6).

These passages are important, for they show that the life of Jesus was a fulfillment of all that the Old Testament looked forward to. There are three main ways in which Jesus is revealed in the Old Testament. For simplicity and clarity, we will call them prophecies, appearances, and symbols.

First, prophecies: Jesus was the promised Messiah, the long-awaited Saviour of God’s people. Hundreds of years before his birth, God sent prophets who foretold many things about the Messiah, all of which were fulfilled in the life of Jesus. Just a few examples would include his birth in Bethlehem (Micah 5:2), heralded by a star (Numbers 24:17); his conception by a virgin (Isaiah 7:14); his flight to, and return from, Egypt (Hosea 11:1; cf. Matthew 2:15); his death by crucifixion, and his resurrection (Psalm 22:1-18; Isaiah 53).

Second, appearances: “the LORD appeared to [Abraham] by the oaks of Mamre, as he sat at the door of his tent in the heat of the day. He lifted up his eyes and looked, and behold, three men were standing in front of him” (Genesis 18:1-2). Many Biblical scholars understand this to be an actual appearance of Christ, the Son of God. The Second Person of the Trinity comes to Abraham in the appearance of a man. Puritan John Gill wrote that, “the truth of the matter seems to be this, that one of them was the son of God in an human form, that chiefly conversed with Abraham…and the other two were angels in the like form that accompanied him in that expedition….”* This happens throughout the Old Testament. When Jacob wrestled with a “man” (Genesis 32:24), the patriarch himself concludes, “For I have seen God face to face, and yet my life has been delivered” (v. 30). Often, when “the Angel of the Lord” appears to God’s people in the Old Testament (for example, Gideon, in Judges 6, or Manoah in Judges 13), he is also referred to as “the LORD” or “God.” Biblical scholars suggest that these are appearances of Christ, not the Father, or the Holy Spirit, who are never said to appear as humans.

Third, symbols. Many Old Testament passages refer to Christ in an indirect manner, by way of types or symbols. From St Paul, for instance, we learn that even the Israelites wandering in the wilderness knew Christ, and he compares their experience with what New Testament Christians receive in Baptism and the Lord’s Supper:

I want you to know, brothers, that our fathers were all under the cloud, and all passed through the sea, and all were baptized into Moses in the cloud and in the sea, and all ate the same spiritual food, and all drank the same spiritual drink. For they drank from the spiritual Rock that followed them, and the Rock was Christ. (I Corinthians 10:1-4)

The prophet Jonah was a symbol of Christ, as Jesus himself tells us: “just as Jonah was three days and three nights in the belly of the great fish, so will the Son of Man be three days and three nights in the heart of the earth” (Matthew 12:38-40). Think of the ways Jesus is described in the New Testament: “the lamb of God” (John 1:29); “the good shepherd” (John 10:11); “prophet” (Luke 24:19); “priest” (Hebrew 3:1); and “king” (Matthew 2:2; 27:11). Yet God had given to the people of Israel lesser prophets, priests, and kings, as well as sacrificial lambs. In addition, there are shepherds in the Old Testament, like Jacob, David, and Amos. So, when we read the Scriptures, and read about a lamb, a shepherd, a prophet, a priest, a king (and these are just a few examples), we should think of Jesus, and see what we can learn about Him from these types and symbols.

In doing this, we should let the New Testament be our guide. Even the simple tool of a good reference Bible can help. When the New Testament quotes a passage from the Old Testament, or the margins list an Old Testament reference, look it up. It will enhance your ability to help children understand the significance and context of whatever passage you are teaching.

The Bible is essentially one book, one story, though made up of many individual books and stories, just as the tales of Lancelot, Galahad, and Gawain are all parts of the legend of King Arthur. Jesus Christ, the Son of God, is at the centre of the Bible’s story.

Look around at the landscape painted by Scripture, and on every hill, in every valley, in every wood and plain, there is Christ. Hear the story of God’s people, and in every scene, at every moment, there is Christ. Read the scriptural account of God’s work in history, and on every page, in every song and letter, there is Christ.

With this understanding, all of Scripture takes on a new significance for parents and teachers. We come to see, for example, that the story of David and Goliath is not primarily about “how to conquer the giants in our lives.” Rather, this story is told because it is a significant moment in the life of David, the ancestor of Christ, who was the Son of David (Matthew 1:1; 9:27). Adam’s story foreshadows the Second Adam, Christ (I Corinthians 15:45). Moses points ahead to One greater than Moses (Hebrews 3:1-6). All of this ought to infuse our teaching with life and energy, with drama and wonder. All is about Christ. Every book, every chapter, every passage, every verse, no matter how difficult or obscure, ultimately finds meaning in union with the story of Jesus Christ. As the Apostle Paul put it, “For from him and through him and to him are all things” (Romans 11:36). Children, with this understanding of the Bible, will not be bewildered at the vast array of stories and characters, but will begin to see this diversity as part of the unity of the One Story, the story of Christ. Add to that the fact that it is, above all, a true story, and you have (of course!) the greatest tool for the transformation of young lives that could ever be imagined.

*From the commentary on Genesis 18 in John Gill’s Exposition of the Bible, which can be found here.

Saturday, October 01, 2005

Tolkien and Lewis Resources

What follows is a short list of resources—books, films, CDs, websites—that are recommended for those who would like to delve deeper into the lives of Tolkien and Lewis, the worlds of Narnia and Middle-earth, and some of the thoughts and ideas that shaped those worlds.

Books:

Bradley J. Birzer

J. R. R. Tolkien’s Sanctifying Myth: Understanding Middle-earth

Devin Brown

Inside Narnia: A Guide to Exploring The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe

Kurt Bruner and Jim Ware

Finding God in The Lord of the Rings

Finding God in the Land of Narnia

Humphrey Carpenter

J. R. R. Tolkien: A Biography

David Day:

A Guide to Tolkien

Colin Duriez

A Field Guide to Narnia

The Inklings Handbook: The Lives, Thought and Writings of C. S. Lewis, J. R. R. Tolkien, Charles Williams, Owen Barfield and their Friends

Tolkien and C. S. Lewis: The Gift of Friendship

The J.R.R. Tolkien Handbook: A Concise Guide to His Life, Writings, and World of Middle-earth

Paul F. Ford

Companion to Narnia: A Complete Guide to the Enchanting World of C.S. Lewis’s The Chronicles of Narnia

Douglas Jones and Douglas Wilson

Angels in the Architecture: A Protestant Vision for Middle Earth

C. S. Lewis

The Letters of C. S. Lewis

Letters to Children

Surprised by Joy: The Shape of My Early Life

The Four Loves

An Experiment in Criticism

The Discarded Image: An Introduction to Medieval and Renaissance Literature

Boxen: The Imaginary World of the Young C. S. Lewis

The Complete Chronicles of Narnia

Of Other Worlds: Essays and Stories

The Ransom Trilogy (Out of the Silent Planet, Perelandra, That Hideous Strength)

The Pilgrim’s Regress

Mere Christianity

Miracles

Till We Have Faces: A Myth Retold

Kathryn Lindskoog

Journey Into Narnia

C. S. Lewis: Mere Christian

Light in the Shadowlands: Protecting the Real C. S. Lewis

How to Grow a Young Reader: Books from Every Age for Readers of Every Age (with Ranelda Mack Hunsicker)

George MacDonald (the author that C. S. Lewis called his ‘master’)

Phantastes

The Princess and the Goblin

The Princess and Curdie

At the Back of the North Wind

The Gifts of the Child Christ & Other Stories and Fairy Tales

Michael D. O’Brien

A Landscape With Dragons: The Battle for You Child’s Mind

Joseph Pearce:

Tolkien: A Celebration

Frederick Rebsamen

Beowulf: A Verse Translation

Tom Shippey

The Road to Middle-Earth: How J. R. R. Tolkien Created a New Mythology

J. R. R. Tolkien: Author of the Century

Mark Eddy Smith

Tolkien’s Ordinary Virtues: Exploring the Spiritual Themes of The Lord of the Rings

J. R. R. Tolkien

The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien

The Silmarillion:

The Hobbit (The Annotated Hobbit is highly recommended)

The Lord of the Rings

Roverandom

The Father Christmas Letters

Mr Bliss

Tree and Leaf: Including the Poem Mythopoeia, the Homecoming of Beorhtnoth

Morgoth’s Ring (The History of Middle-earth, Volume X. See especially ’Athrabeth Finrod Ah Andreth’, which sheds much light on the Christian foundations of Tolkien’s mythology)

Turgon (from theonering.net)

The Tolkien Fan’s Medieval Reader (Texts of many of the Old English, Middle English, Old Norse, and Celtic tales that shaped Tolkien’s stories)

Recordings:

BBC

The Hobbit (Radio adaptation)

The Lord of the Rings (Radio adaptation)

Focus on the Family Radio Theater

The Chronicles of Narnia (Paul McCusker’s excellent radio adaptation of all seven books)

R. C. Sproul, Jr.

Further Up and Further In: Studies in Narnia (CD set)

Basement Tapes #24: You Don’t Know Jack (CD set on C. S. Lewis)

Douglas Wilson

What I Learned in Narnia (CD set)

Periodicals:

Christian History Magazine, Spring 2003: Tolkien: Man Behind the Myth

Credenda/Agenda: Volume 13, Issue 5: Jack: A Reformed Appreciation of C. S. Lewis

St Austin Review, January, February 2003: Tolkien Revisited (see especially Bradley J. Birzer’s fine article, ‘Grace and Will in Tolkien’s Legendarium’)

Websites/web articles:

theonering.net (fan site)

lordoftherings.net (official movie site)

narniaweb.com (official movie site)

cslewis.drzeus.net (Into the Wardrobe: C. S. Lewis site)

tolkienlibrary.com (the books of Tolkien)

christianitytoday.com/history/newsletter/2003/aug29.html (This is an interview with Colin Duriez on the friendship of Tolkien and Lewis. At the bottom of the page are links to a number of other articles, including a fascinating email conversation between Bradley J. Birzer and Mark Eddy Smith)

Video:

The Chronicles of Narnia (TV adaptations by the BBC of four of the seven books)

The Lord of the Rings (Big screen adaptations directed by Peter Jackson)

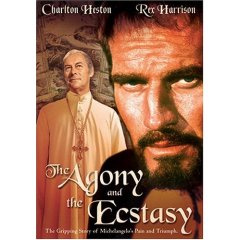

The Agony and the Ecstasy

Just wanted to mention something that is actually rather old news, though I just found out about it. One of my favourite movies was finally released on DVD earlier this year. The Agony and the Ecstasy, starring Charlton Heston as Michaelangelo and Rex Harrison as Pope Julius II, tells the story of the painting of the Sistine chapel. I hope to write a review later for the Logres Hall Classic Reviews page, but for now just wanted to mention it here. My previous copy was a cheap pan and scan ('This movie has been formatted to fit your screen'; it's not widescreen, in other words) VHS with terrible audio and picture quality. The DVD is a restored version of the film and it is truly glorious. There is so much I had really never seen before. A great film about issues of art, life, and faith, and some of the best acting you are likely to see anytime soon. Superb script, too. Highly recommended.

Thursday, August 18, 2005

Patch the Pirate and "Reality"

The following was a comment one of Cloud’s readers made in response to the original article, and this is what I wanted to talk about:

"I have a very strong position that is in opposition to ‘Patch’, but for reasons not mentioned in your article. ‘Patch’ is based on Non-Reality. This is a very dangerous foundation upon which to ‘minister’ to young people. Bible-believing Christianity is REAL, not fantasy as presented by ‘Patch’. Nowhere in the Bible do you find Bible truth presented in fantasy form. This false method of ‘evangelism’ or ‘teaching’ leads young people into a fantasy world, not into the reality of true Christianity. To add to this error, the hero ‘Patch’ is a pirate. I can find no pirate in all of history that is good. Is this calling ‘good’ ‘evil’? This type of ‘ministry’ is a bane on the church. Dobson does the same thing with his ‘Odyssey’ program. I would like to see someone research this and present it through your medium. I deeply appreciate your ministry. God bless you, my dear Brother."

I actually deal more at length with this kind of criticism of fiction in my forthcoming book Talking of Dragons, but here are a few thoughts.

First, the writer asserts his opposition to Patch the Pirate on the indisputable grounds that it is “based on Non-Reality.” He asserts that this is a “dangerous foundation upon which to ‘minister’ to young people.” He supports this assertion with another assertion: “Nowhere in the Bible do you find Bible truth presented in fantasy form. This false method of ‘evangelism’ or ‘teaching’ leads young people into a fantasy world, not into the reality of true Christianity.”

Taking these statements together, then, it seems that by fantasy the writer means Non-Reality. Presumably, what he means is that the events in the Bible really happened, while the events of Patch the Pirate, Adventures in Odyssey, etc., did not, and thus should be categorized as “Non-Real.” Now to begin with, I wholeheartedly agree that the Bible is primarily a book of history. I accept without qualification the historicity of the miracles of the prophets, Christ, and the apostles, including the great miracles of the Virgin Birth and the Resurrection of Christ. In this sense, the Bible stories are “Real,” while fictional stories are “Non-Real.”

The question has to do with whether fictional stories are really, as the writer claims, “dangerous.” Since he asserts that, “Nowhere in the Bible do you find Bible truth presented in fantasy [fictional] form,” I presume he would change his mind if we could show him examples of just such “Non-Reality” in the Scriptures themselves. This I intend to do. So let’s just briefly mention a few examples of passages that the Anti-Patch writer would have to cut from his Bible to avoid such “dangerous” “Non-Reality.”

In II Samuel 12:1-7, we have the prophet Nathan’s story of the rich man stealing the poor man’s lamb. He told this story to King David after his adulterous affair with Bathsheba, and the murder of her husband, Uriah the Hittite. Nathan comes to confront David but does so obliquely (at first) by telling him a fictional story. Ultimately, the story was true, in the sense that David had done, in effect, the same thing as the man in the story. But then, the same could be said of most fictional tales. The fact remains that there really was no rich man who had stolen a poor man’s lamb. What really happened (and remember Anti-Patch’s insistence on only the “REAL”) was that a king had stolen a soldier’s wife. Why couldn’t Nathan just stick to reality? Obviously, because one benefit of fiction is that it helps us see truth and reality that we would otherwise have missed. By telling David a fictional story of a gross injustice, Nathan stirred David’s righteous anger to the point of admitting that the man in the story deserved to die. Then, the kicker: David, “thou art the man.” Can you imagine a more powerful way to turn the mirror on a man’s soul, driving him to his knees in repentance before a holy God? Such is the power that God has given to Story.

Other examples could be multiplied. In Revelation, God shows John visions of things that even the most conservative of scholars admit are often symbolic (i.e., the most die-hard literalist Baptist does not believe that the Anti-Christ has ten horns and seven heads). These symbols are true, in the sense that they point to something beyond them that is true, but the symbols themselves are, strictly speaking, imaginary, fantastical, and fictional. Yet if we live by Anti-Patch’s arbitrary insistence on only “REAL” events, we will miss nearly everything that the book of Revelation has to teach us about God’s sovereignty and triumph over His enemies, because we would not be allowed to read Revelation.

Most tellingly, we have the parables of Jesus Himself. These are short, fictional stories designed to teach truth for those who have ears to hear, and to confuse those who do not (Matthew 13:9-16). Shouldn’t Jesus just have stuck to teaching eternal truths, as in the Sermon on the Mount? Why delve into “Non-Reality”? The same reason Nathan told David a story instead of jumping right to the “Thou art the man,” as many contemporary “prophets” would have done: Story is powerful. Now, some may say that Jesus, being God, could have known of true stories in which a woman lost a coin, or an enemy sowed weeds among the wheat, or a man was robbed, ignored by his countrymen, and then helped by a foreigner. Granted. But Jesus doesn’t present them that way, as if they were AP news stories. He doesn’t tell us the names of the people involved, as the Bible usually does when recounting true history. The point of these stories is that they apply to everyone, because they could have happened to anyone.

Finally, just a word on Anti-Patch’s condemnation of Patch the Pirate on the grounds that he is a pirate. I find it hard to imagine that children will suddenly develop a desire to loot and pillage after listening to Patch. Obviously, this is not a pirate in the sense of “we extort, we pilfer, we filch and sack, drink up me hearties, Yo ho!” There are other, symbolic (there’s that nasty, Non-Real word again) ways to use the image of a pirate. Michael Card’s haunting song, Why, comes to mind: “Why did it have to be a heavy cross He was made to bear?…It was a cross, for on a cross, a thief was supposed to pay. And Jesus had come into the world to steal every heart away.” Or, more interestingly, we have another of Jesus’ fictional parables, in which He says, “how can someone enter a strong man's house and plunder his goods, unless he first binds the strong man? Then indeed he may plunder his house” (Matthew 12:29). The hero of this parable actually enters someone’s house and “plunders” it (“steals,” “loots,” “pillages,” “sacks,” are listed by Merriam-Webster as synonyms, though they forgot to add, “drink up me hearties, Yo ho!”). So, it would seem the image of a thieving marauder can be used to good purpose in fictional stories, obviating both of Anti-Patch’s criticisms in one fell swoop.

Yo ho, Yo ho, a pirate’s life for me.

Sunday, August 07, 2005

Poetry - Old as Mountains

*This is what philosophers of earlier eras called a joke, though they may have spelled it differently.

William Chad Newsom

Learn now the lore of living creatures

All the elders of this earth unmade

Threescore and Ten to thrive under Heaven

Passing privilege to ply our trade

But there are those whose thoughts reach further

Beyond the years, the yesterdays of all

And standing still, like stone unmoving

Won’t see the setting of the sun’s last fall

Chorus:

Mark the memory, immortal fountains

Of the ancient ones, old as mountains

I’m seeking signs, a sight of glory

A little lower than the lords on high

I’ll look for lore of lost Long-livers

Await the wisdom of the Wielder’s cry

And now I know, for none have perished

Of all the ancient Sires of Earth’s great stage

They walk at will, the Wielder’s heralds

Behold the Harvest of the Heav’nly Page

Chorus

Mark the memory, immortal fountains

Of the ancient ones, old as mountains

(Instrumental)

Chorus

Mark the memory, immortal fountains

Of the ancient ones, old as mountains

Repeat Chorus

Of the ancient ones, old as mountains

Oh, the ancient ones, old as mountains

Ent the Earthborn, old as mountains

Thursday, August 04, 2005

Thoughts on Harry Potter, Part I

I must begin this effort with a caveat: I think that sweeping conclusions on the meaning of the Potter books both hasty and unwise, until the final book has been published. This is because J.K. Rowling, author of the series, is all about surprises, and we may find that the seventh volume is the left hand that takes away what the right hand has given. This will almost certainly be true in some ways (just whose side is Snape on, anyway?), and may be true in bigger ways than we can now guess, though one hopes the final book won’t yank all available rugs as, say, the final film in The Matrix did (reportedly: I have not seen it, having lost interest in the series during the second film). Because of this, I will be cautious about big conclusions, offering instead what I hope to be food for thought, interaction on the Potter books and the controversy swirling around them.

'It’s wonderfully quiet here. Nothing seems to be going on, and nobody seems to want it to. If there’s any magic about, it’s right down deep, where I can’t lay my hands on it, in a manner of speaking.'

‘You can see and feel it everywhere,’ said Frodo.

‘Well,’ said Sam, ‘you can’t see nobody working it…I would dearly love to see some Elf-magic, Mr. Frodo!'

Magic, for Tolkien, was actually Art, without the normal human limitations. It was anything but sorcery or witchcraft. While Granger seems to be right in his assertion that Potter magic is not sorcery, I can’t help but think that Tolkien would not have cared for the more scientific magic we find at Hogwarts. Still, as I said, the seventh book is not yet written, and Rowling now seems to be hinting that there is something greater than this laborious, scientific approach to magic. In Half-Blood Prince, Harry and his friends are beginning to learn non-verbal spells, which is perhaps a little closer to the unseen magic of Lothlorien. And Dumbledore suggests that all the accoutrements and paraphernalia of magic are only for the wizarding novices, not for those who have truly mastered their gifts at incantational power. I truly hope there are further developments like this in the final book.

Wednesday, June 29, 2005

What I'm Watching

Second is The Forgotten. This came out last year, I believe, and I saw it recently on DVD. This is a fairly creative suspense/thriller with some unexpected punches, not the least of which is a surprisingly vivid pro-life message. It also highlights a key Biblical theme, which is that of remembering (Deuteronomy 32:7; I Chronicles 16:12; Psalm 78; Psalm 88:12). In a key moment, one character says, "there are worse things than forgetting." The main character responds, "No, there aren't." A wild ride, and thoroughly worth the time.

Third, The Incredibles. Saw it on DVD for the first time recently. Very unusual, for a super-hero movie. Not many in this crowded genre will go out of their way to praise the virtues of family life, or skewer American egalitarianism, or what one character describes as "new ways to reward mediocrity." Another time, one character says that "everyone is special," to which an insightful child replies, "which is another way of saying that no one is." As I say, rare stuff. In one deleted scene, which is included in the special features, a mother blasts a smart-mouthed "professional woman" for suggesting that being a mom and homemaker is throwing away life. But it's not just the Christian and moral themes: the animation is stunning, the writing is stellar, and the characters are staggering (so much for the alliteration). A thoroughly enjoyable piece of work, and the bad guy (Warning: spoiler ahead!) eats it in the end, blasted to smithereens in a most satisfying conclusion. I'm with C.S. Lewis on this: let the witches, giants, dragons, super-villains, etc., be soundly killed at the end. How else can we teach our children about the utter folly and certain death of Evil?

Sunday, June 26, 2005

What I'm Reading

Second is Charles Williams' Taliessin Through Logres. This is his cycle of Arthurian poems, and it is brilliant. It is also very heavy reading, and not something to begin (as I did, first go-round) when you are particularly tired. This is not because it is boring, but because it requires especially alert eyes to be able to see even a few of its majestic beauties. The book includes Williams' own unfinished (and you should know that even the work as a whole was unfinished at his death) prose study of the Arthurian Legend, and C.S. Lewis' indispensable commentary on the work. I have been reading along with Lewis while working through the poems, and, at least for a beginner, this is the only way to fly. Highly recommended, though difficult to obtain: I ran across this by chance, as we say in Middle-earth, in a used bookstore not long ago, and was plum pleased with my treasure-hunting skills.

Saturday, June 25, 2005

The Princess and the Goblin

A Short Review

William Chad Newsom

I just finished reading George MacDonald's book-length fairy tale for children, The Princess and the Goblin. Here at Logres Hall, we encourage regular reading of fairy tales as a way of reinforcing both the doctrine and morality of the Bible. MacDonald's book is a good example of that, especially in the way it skewers naturalism and praises faith through the character of Irene (the princess) and her relationship with her great-great-grandmother.

Tuesday, June 21, 2005

New Logres Hall Website!

Thoughts on the Death of Pope John Paul II

Thoughts on the Death of Pope John Paul II

"Doctor Martin, if you leave the Christian to live only by faith; if you sweep away all good works, all these glorious things you dismiss as mere 'crutches,' what will you put in their place?"

Johann Staupitz to Martin Luther, in the 1953 film, Martin Luther

There are undoubtedly a plethora of thoughts and emotions swirling through the minds of those who would describe themselves as Protestants or Evangelicals at the news of the Pope’s passing. Everything from, “that’s so sad,” to “John who?” to “die, Papal devil! Ya-hoy!” I found myself experiencing a curious (though not completely unfamiliar) sensation: a wild desire to run straight to the local Catholic Church and bow in submission to Mother Church.

Strange, you say? Horrifying, you think? Perhaps not. Interest in the Pope and the Roman Catholic Church will certainly be at a peak now, until the novelty wears off, anyway. Many Protestants may feel a similar stirring. But I think there was something deeper at work here. In fact, having given it some thought, I am inclined to elevate my experience to a proverb: “he who feels no emotional inclination to join Rome after the death of a good pope has a view of the Church that, were that view a movie-goer, would never be able to see the film over the heads of those in front of him.” Or something like that. It’s too low, in other words (his view of the Church, I mean).

Put another way, we Protestants and Evangelicals ought to lament all that we have lost by our separation from Rome. Not that we don’t also recognize that there was much that needed to be lost: Rome has many errors, but the proper response to those errors ought not be a haughty, “God, I thank thee that I am not as other men are, or even as this Catholic.” Rather, we should mourn and grieve for the falsehoods that keep us at arm’s length from our brothers and sisters in the Roman communion—their errors, and ours as well. And we should readily admit that, as Peter Leithart recently said of John Paul,

"Flawed though his theology was, he remains far and away the greatest Christian leader of the past century. No Protestant comes anywhere close. Billy Graham may have preached more (maybe!), but Graham had nowhere near the political weight or the theological depth of Pope John Paul II. John Paul II's life is not only testimony to the wonders that God can perform through imperfect instruments but an inspiration for all Christians, whether or not we aspire to pope."

If Rome has forgotten the justification of God, Evangelicals have forgotten the beauty of God. If Rome has falsely elevated Tradition, Evangelicals have falsely denigrated it. Where Rome has given overmuch reverence to Saints, Evangelicals still think Saints come from New Orleans. We have much to learn. Some will think such words a compromise with false doctrine (the “Papal Devil” crowd). So be it. If they want to lump Chesterton, Tolkien, and John Paul in with Hitler, Nero, and LaVey, they’re welcome. They would probably do the same to Luther and Calvin, too. But R. C. Sproul, Jr. (no closet Papist, he) recently managed to write both these statements in the same article:

"I believe that Rome is an apostate church which preaches a false gospel."

"God’s grace isn’t constrained to flow only in those places where His gospel is rightly proclaimed."

R. C. is right, on both counts. And we cannot, of course, return to Rome: not yet, anyway. Not until God is pleased to bring both Reformation and Revival to his wayward Church. When Rome and Evangelicalism have duly repented of their sins, the Church may—nay, someday it will—be one again. It was while working through these Romanish thoughts that I dug out my old VHS copy of the 1953 film Martin Luther, in which the line at the top of this post was delivered. So what was Luther’s answer? Just what would he set in the place of the “crutches” of relics and indulgences?

“Christ,” was Luther’s simple answer in the film’s best moment. “Man only needs Jesus Christ.”

This is what our Roman Catholic brothers and sistersneed to realize, even as we mourn with them the passing of a pope who might havesoftened even the heart of a Wittenberg monk. When we cry “sola fide!” (“Faithalone”) it is only ever in the light of “solusChristus!”(“Christ alone). We say Rome has denied, whetherwittingly or no,sola fide,but we are not passing through the fire andtumult of religious controversy to win the right to install correct sentences inpeople’s brains.Sola Fideis vital because to deny it is to denySolus Christus.AndChristusis not a proposition: He is the Sonof Man, the Lord of Glory, Yahweh veiled in human flesh, the very TrinityIncarnate. “Faith alone” must ever be our battle cry, until God grants somefuture pope repentance, and we are again one, because “Faith alone” points everto the Christ of “Christ alone.”