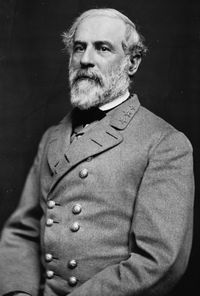

Today is the 200th anniversary of the birth of a man who (it should not be so difficult to say) is certainly one of the greatest Americans in history: General Robert Edward Lee. It is only difficult because our culture does not understand honour and righteousness as well as it once did. Lee was a man of almost unbelievable honour and integrity. After the war, he did, as one biography put it, more than any other American to heal the divisions between North and South.

Today is the 200th anniversary of the birth of a man who (it should not be so difficult to say) is certainly one of the greatest Americans in history: General Robert Edward Lee. It is only difficult because our culture does not understand honour and righteousness as well as it once did. Lee was a man of almost unbelievable honour and integrity. After the war, he did, as one biography put it, more than any other American to heal the divisions between North and South.We celebrated with our children by watching Ron Maxwell’s fine film, Gods and Generals. Focussing attention on three battles in the first two years of the War Between the States—First Manassas, Fredericksburg, and Chancellorsville, the movie portrays the greatest military partnership of all times, that of General Lee with his ‘right arm,’ commander of the second corps of the Army of Northern Virginia, General Thomas Jonathan ‘Stonewall’ Jackson.

There are many fine moments in the film, including a heart-wrenching battle before the stone wall at Fredericksburg between two Irish regiments: one Northern, one Southern. ‘Don’t they know we’re fighting for our freedom?’ cries a Southern Irish officer, incredulous that his old countrymen could be fighting for the Yankees. ‘Didn’t they learn anything at the hands of the English?’ ‘These Irish Rebels are our countrymen,’ shouts the Northern Irish officer, even as he urges his men on in their hopeless charge. But one of the most telling moments in the film is also just before the battle of Fredericksburg, when Colonel Joshua Chamberlain of the Twentieth Maine (later to earn lasting glory for his heroic defence of Little Round Top at the Battle of Gettysburg), speaks to his men before the battle, just as the vanguard of the Union forces are crossing the Rappahannock river into Virginia. Maxwell puts into Chamberlain’s mouth the words of Marcus Lucanas, Roman poet, chronicling the military crossing of the Rubicon (an act unlawful under Roman law) by Julius Caesar. I say it is telling, because at the same moment as this speech, the Union Army of the Potomac is also crossing a river, and invading their own country. Notice the italics, which are my own, and ask your self whether Maxwell’s intention as a screenwriter and as a director could be clearer:

In the Roman civil war, Julius Caesar knew he had to march on Rome itself, which no legion was permitted to do. Marcus Lucanus left us a chronicle of what happened. ‘How swiftly Caesar had surmounted the icy Alps, and in his mind conceived immense upheavals, coming war. When he reached the little Rubicon, clearly through the murky night appeared a mighty image of his country in distress; grief in her face, her white hair streaming from her tower-crowned head. With tresses torn and shoulders bare, she stood before him and sighing, said: “Where further do you march? Where do you take my standards, warriors? If lawfully you come, if as citizens, this far only is allowed.” Trembling struck his limbs, and weakness checked his progress, holding his feet at the river's edge. At last he speaks. “Oh, thunderer, surveying great Rome's walls from the Tarpeian rock. Oh, Phrygian, house gods of Lulus, clan and mysteries of Quirinus, who was carried off to heaven. Oh, Jupiter of Latium, seated in lofty Alba and hearths of Vesta. Oh, Rome, equal to the highest deity, favor my plans. Not with impious weapons do I pursue you. Here am I, Caesar, conqueror of land and sea, your own soldier everywhere, now too if I am permitted. The man who makes me your enemy, it is he will be the guilty one.” He broke the barriers of war and through the swollen river swiftly took his standards. When Caesar crossed the flood and reached the opposite bank from Hesperia 's forbidden fields, he took his stand and said: “Here, I abandoned peace and desecrated law. Fortune, it is you I follow. Farewell to treaties. From now on, war is our judge.”

Hail Caesar. We who are about to die salute you.'

Maxwell compares Lincoln’s armies to Caesar, unlawfully inciting war against his own countrymen, and feeble pleas of patriotism (‘O Rome, equal to the highest deity…the man who makes me your enemy, it is he will be the guilty one’) his only excuse. He tells us that the North, ‘abandoned peace and desecrated law,’ and said ‘farewell to treaties…from now on, war is our judge.’ Implicitly, the South is the 'mighty image of his country in distress,’ pleading for peace. In the movie, Southerners, like Jackson, quote Scripture, while Northerners, like Chamberlain, quote pagan (albeit beautiful) poetry. The meaning is clear enough, and the sympathies of filmmaker Maxwell (blessings upon him), equally clear (though certainly he would also sympathise with many of the fine soldiers—like Chamberlain and General Winfield Hancock, for instance— in the Union forces as well). It is a fine movie, and a fine way to celebrate the birth of one of our great national and Southern heroes, Robert E. Lee.

The War Between the States was one of the saddest, most glorious, beautiful, horrifying, tragic, noble moments in our country’s history. We are fools if we ignore its stories, or its lessons. Let this day be a reminder to us of our own history, and especially of the nobility of this great and good man.

3 comments:

God Bless Ya (Cesar Vidal)

The intent of Maxwell is clear to you, perhaps only because you share the bias that you ascribe to him. No doubt that he has sympathies for the South, but Chamberlain's recital of Lucanus is not a demonstration of that which was wrong with the purpose of the North at that time. Rather, it is a demonstration of the conviction of the Union soldiers that while knowing that what they were doing was sacrilege on its face, it was none-the-less righteous in the face of a higher standard. As Caesar cross the Rubicon in violation of Roman law, he did so in the belief that the law itself in that part of the Republic had been corrupted and that his mission itself was divine. So too did the Union feel that while marching with an Army within the United States was wrong, and that to march on the municipal homelands of their countrymen and bretheren was wrong, that it was none-the-less necessary to quell and even greater wrong.

Great Post. Long live the memory of General Lee.

Post a Comment